HIDDEN

HISTORY

RECOUNTING THE

SHANGHAI JEWISH

STORY

Curated by Holocaust Museum LA, this never-before-seen exhibition entitled “Hidden History: Recounting the Shanghai Jewish Story” tells the little-known history of the diverse, resettled Jewish community in Shanghai, including Iraqi Jews who arrived in the mid-1800s, Russian Jews who fled pogroms at the turn of the century, and German and Austrian Jews who desperately escaped the Nazis. With most countries limiting or denying entry to Jews during the 1930s, the free port of Shanghai became an unexpected safe haven for Jews attempting to flee the antisemitic policies and identity-based violence in Nazi-controlled Europe.

“Hidden History” explores this multifaceted history of desperation, loss, and asylum through survivor stories and the photographic lens of prominent American photojournalist Arthur Rothstein, who documented the Shanghai Jewish community in 1946 for the United Nations. The exhibition highlights their stories of survival and features vibrant artifacts from the Holocaust Museum LA's collection, as well as those on loan from the Skirball Cultural Center, Yad Vashem, and the Arolsen Archives in Germany.

JEWISH LIFE IN CHINA

From the second century BCE until the perfection of maritime trade, the Silk Road served as the major conduit across Europe, Africa, and Asia. Jewish merchants had the unique ability to communicate with regional Jews across the Silk Road who would then translate between their lingua franca, Hebrew, and local languages; thus, they easily traveled, traded, and communicated across the continents. The first established Chinese Jewish community settled in Kaifeng, a bustling center for trade, communication, and transportation, and at the time, the capital of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127).

Kaifeng Kippah

Courtesy of the Skirball Museum, Skirball Cultural Center, Gift of Nancy and Alan Block

BAGHDADI JEWS:

THE FIRST JEWISH COMMUNITY IN SHANGHAI

In 1842, the Treaty of Nanjing ended the Opium War between Great Britain and China and opened five Chinese cities to international trade, establishing Shanghai as an open port for foreign business and settlement. Seeking both an escape from antisemitic persecution as well as the expansive work opportunities a new port city like Shanghai offered, Baghdadi Jewish immigrants migrated and settled in the city. They maintained Jewish customs, founded schools and synagogues, established youth groups, and created a rich, unique way of life. Prominent Baghdadi Jewish families, such as the Sassoons, Kadoories, Hayims, and Hardoons achieved economic success, establishing vast business empires and expanding trade.

David Sassoon & Sons

c. 1850

HARBIN JEWISH COMMUNITY

The Russo-Manchurian Treaty of 1897 allowed Russia to expand the Trans-Siberian Railroad with the Chinese Eastern Railway. Harbin, a village in Manchuria, grew as the administrative center for the railway construction and, along with Tianjin and Shanghai, became a desirable place for Jews seeking work opportunities as well as an escape from oppression. By 1903, the year the rail line opened, a self-administered Jewish community of about 500 was already established in Harbin. The Harbin Jewish population continued to grow with waves of refugees fleeing pogroms and brutality during World War I, the Russian Revolution, and Russian Civil War. Jewish life in Harbin peaked in 1930 with tens of thousands of Jews calling the city home. The Japanese occupation of Manchuria in 1931 drastically impacted the community, resulting in many Jews leaving to other parts of China, including Shanghai.

Dora Ozer, born in Harbin, with friends on a beach

c. 1930s

ESCAPING NAZI DESTRUCTION

Europe was home to a set of dynamic, diverse Jewish cultures for over 2,600 years, most of which was decimated during the Holocaust (1933-1945). Within weeks of coming to power, Hitler dismantled democracy and paved the way for a totalitarian, antisemitic government, enacting the first discriminatory anti-Jewish laws in April 1933. The Nazi government enacted thousands of prejudicial laws to restrict the civil and human rights of Jews living under their control. These dehumanizing laws segregated and isolated Jews from society and deteriorated their everyday lives. Following Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria in March 1938, these antisemitic policies were quickly extended to Austrian Jews, sparking a refugee crisis as Jews living under Nazi control desperately tried to emigrate. Though seemingly an unlikely refuge, Shanghai, as an international port city, required no entry visa, becoming one of the only options for German and Austrian Jews trying to escape the brutal violence.

Destroyed shop owned by a German Jew following Kristallnacht

Nov. 1938

SANCTUARY IN SHANGHAI

By the 1930s, Shanghai, the hub of China’s international trade, was the fourth largest city in the world. What began as a trickle of approximately 1,500 Jewish refugees from Europe, soon developed into a flood, with numbers jumping to 17,000 by the end of 1938.

Prior to the waves of refugees arriving in 1938, the Mizrahi and Ashkenazi communities had created their own institutions and organizational structures. However, these two established communities cooperated to provide a massive aid effort for the anguished Jewish refugees who managed to reach Shanghai. The Committee for the Assistance of European Jewish Refugees was established in October 1938 by community leaders who established accommodations, soup kitchens, and financial aid.

MEDAVOY

MEDAVOY FAMILY

Dora Medavoy (née Ozer), born on May 24, 1921, in Harbin, was the youngest of 15 children born to parents Moses and Bertha, originally from Odessa. After Moses passed away in 1926, Bertha, Dora, and two of her siblings went by train, first to Tianjin to stay with Dora’s older sister, and then to Shanghai. Dora worked in fashion, taking measurements in a corset store, and in 1939, she met Michael Medavoy at the Shanghai branch of Betar, a youth Zionist movement. Michael, born in Ukraine in 1918, had immigrated with his family to Shanghai as the city was found to be free of antisemitism.

As a young couple, Michael and Dora enjoyed the cosmopolitan city, attending parties and dances, and socializing with friends. The pair were married in 1940 at the Ohel Rachel Synagogue (built by the Sassoons, it still stands today) and settled among the Russian Jewish community. Dora opened a clothing store and Michael worked as a mechanic, becoming a manager at the Shanghai Telephone Company. The couple had two children, Mike, in 1941, and Veronica, in 1947.

As the Shanghai Jewish community quickly mobilized to provide aid to the influx of refugees, Betar, of which Michael and Dora were members, helped receive the refugees and transported vital supplies. Michael was a member of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps, a group that volunteered to protect Jewish refugees while supporting the Shanghai Municipal Police.

Following the end of the war, the Medavoys secured passage to Chile in 1947, as strict immigration quotas in the U.S. made it difficult to obtain a visa. They eventually immigrated to the U.S. in 1957.

HONGKEW GHETTO

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the subsequent outbreak of war in the Pacific Theater, impacted life for both the established Jewish community as well as the resettled refugees, as the Japanese military occupied and took control of the entire city. Those with Dutch, British, or American ties were sent to prison camps. Property was confiscated, bank accounts were frozen, and many of the newly established newspapers ceased publication.

Under continued, intense pressure from their ally, Nazi Germany, Japan issued a proclamation on February 18, 1943, establishing a “designated area” for “stateless refugees.” All Jews who arrived in Shanghai after 1937 were ordered to relocate to a one square mile area in the Hongkew District. The living conditions in the ghetto were horrific; electricity, coal, and food were rationed and in short supply, malnutrition was common, and the overcrowded and unsanitary conditions led to rampant diseases like typhus. The ghetto boundaries were marked, exits were guarded, and leaving the ghetto was illegal without a permit. Those applying for a permit faced abuse and humiliation by Japanese officers Ghoya and Okura, who were symbols of oppression and fear among the Jews in the ghetto. With German, Austrian, and Polish Jews confined to the ghetto all facing the same anguish, cross-cultural relationships and mutual respect formed. Despite different languages and traditions, the desperate circumstances and unknown fate of the refugees united them, and they formed kinship, working together to maintain human dignity.

MAIMANN

MAIMANN FAMILY

Renee Maimann was born March 21, 1927, in Vienna, Austria, to parents, Baruch and Anna Maimann, and older brother, Freddy. When the Nazis annexed Austria in March 1938, life became increasingly difficult for Austrian Jews. Renee could no longer attend school and the Nazis confiscated the family’s assets and home. Desperate to escape, Anna secured visas for Shanghai.

Upon arriving in Shanghai, the family was taken in by various Jewish relief organizations and allocated a small apartment in the Hongkew District. Renee was enrolled at the Kadoorie School and joined Betar, a Zionist youth movement. Her family established Café Klinger, a Viennese restaurant in the area of Hongkew known as “Little Vienna.” The business thrived, up until Japanese forces occupied Shanghai in 1941. Then in 1943, when Jewish refugees were forced into the Hongkew Ghetto, Renee recalled living in constant fear, both of mistreatment at the hands of the Japanese guards and of being killed by U.S. bombers.

After Shanghai was liberated by American forces, Renee secured sponsorship for a visa to the U.S., while the rest of the Maimann family settled in Canada. Renee arrived in Brooklyn and later married Beno Rapaport. The couple had two daughters and settled in Santa Clara, California.

KOLBER

KOLBER FAMILY

Eva and Josef Kolber and their children, Lily and twins Adolf (“Dolfie”) and Walter, lived in Vienna, where they operated a sewing factory and store selling women’s clothing. Following the annexation of Austria, the Kolber’s storefront was often vandalized, and the Gestapo regularly raided the factory. Understanding the imminent danger, Eva and Josef desperately looked to escape, and secured passage to Shanghai. Josef and Eva covertly packed equipment from the factory, sewing valuables into their clothes, and on October 29, 1938, Josef and the boys set off from Trieste, Italy. Eva and Lilly later followed by train and arrived a month later.

In Shanghai, the family found a home, and Eva and Josef established the JEKO Knitting Factory and a clothing store on Nanking Road. At a dance, Lily met Joseph Ozer (the brother of Dora Medavoy) whose Russian Jewish family was originally from Harbin. The pair married and had two children. Dolfie became engaged to Margot Rosengart, a young hairdresser who escaped from Nazi Germany. While studying violin at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, Walter began a secret romance with fellow musician Chao Chen, and the pair later married.

With the Japanese occupation and the establishment of the Hongkew Ghetto, the Kolber’s store was closed. The family was forced to vacate their home and relocated to makeshift quarters above the factory, where they remained till the end of the war. In 1947, Dolfie and Margot immigrated to Bolivia, while Eva and Josef, along with Lily, David, and their children, immigrated to Israel in 1948. Meanwhile, Walter, Chao Chen, and their son Harry immigrated to Austria in 1947.

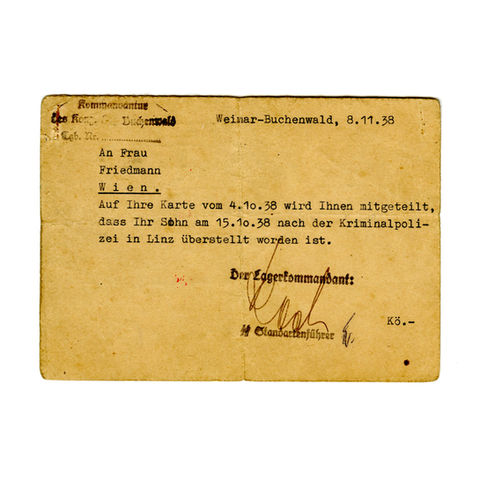

FRIEDMANN

FRIEDMANN FAMILY

Born October 19, 1913, John was the only child of Adolph and Rudolphina. At 13, John’s parents divorced, and he and his mother moved to Vöcklabruck, a small town in upper Austria. In March 1938, when Nazi Germany annexed Austria, Austrian Jews were subjected to extreme intimidation and violence. John’s car was confiscated, and he was forced to give up his business. In April 1938, John was arrested and deported to Dachau, and then to Buchenwald. Fearing for her son’s safety, Rudolphina appealed for help. A friend who was a police official, wrote to the Gestapo falsely stating that John was wanted on criminal charges, and managed to secure John’s release.

John obtained passage for himself to Shanghai, with his mother following sometime later. Upon arrival, John and other refugees were welcomed and housed at the Embankment Building, owned by Sir Victor Sassoon. John found employment, first with the JDC, then as a mechanic for the China General Omnibus Company.

In February 1943, John and Rudolphina were forced into the Hongkew Ghetto where they lived in small apartments lacking water or toilets, and overcrowded unsanitary conditions precipitated a constant fear of disease. Food was scarce and movement in and out of the ghetto was restricted. As an employee of Datsun, John was one of the few able to obtain an exit pass.

Following the American liberation, John worked with the U.S. Armed Forces and later with the JDC. In 1949, John secured passage to Canada, where he got a job in Toronto, and met his wife, Alice. The couple were married in 1950, and settled in Los Angeles, where they raised their daughter, Joyce.

MILLETT

MILLETT FAMILY

Charles Millett (née Karl Sinai) was born in Vienna on November 27, 1937. His father, Ernst, was a tailor, and his mother, Grete Reiss, worked as the office manager in the family-owned iron foundry, Gebrüder Reiss Wien. Following Kristallnacht, the Nazis evicted the Reiss family from their home and arrested Sigmund, Charles’ grandfather, deporting him to a concentration camp; he was never seen again. Grete, Ernst, and baby Charles escaped Vienna, bribing a train conductor to allow them passage to Siberia. From Siberia, they found their only option to be Shanghai, which required no entry visas. They boarded a ship bound for Shanghai, with Grete documenting the trip on her camera. Ernst’s ill health and the strain of their situation eventually took its toll, and the couple separated.

In 1943, Charles and his mother were moved into the Hongkew Ghetto where Charles attended the Kadoorie School. Life was difficult and confusing for Charles who was a young child. Bombings, food shortages, disease, and physical abuse were commonplace. His mother’s hardships were perhaps the darkest of Charles’s childhood memories. A beautiful woman, Grete, was frequently targeted and abused by the Japanese guards.

After WWII ended, Charles and Grete immigrated to Australia. Once they arrived in Sydney, however, they and other Jewish newcomers were met with suspicion and resentment from the local population. At 17, Charles began working as a cook’s assistant to ensure he never went hungry again. This led to a lifelong career in the hotel and restaurant industry. Charles eventually settled in Los Angeles, where he met his wife, Minnie, at a dance. The two happily married in 1964 and had two children.

LIBERATION, LOSS, AND LIFE AFTER

When American soldiers arrived in Shanghai, they were immediately inundated with desperate requests for news from Europe. Refugees soon learned that their homes had been destroyed or claimed by others, most of their families murdered, and their communities devastated. In addition to desperately searching for news of loved ones, they faced the question of how to move forward.

The prospect of rebuilding their lives after liberation was daunting and filled with uncertainty and anxiety. Those who decided to pursue immigration to a new country, found that just as prior to the Holocaust, their options were still limited. Refugees sought help from community leaders who returned from Japanese prison camps and organizations such as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) and the JDC to help find a new home or repatriation back to Europe. By the time of the Communist takeover in 1949, most Jews in Shanghai - Mizrahi and Ashkenazi alike - had immigrated to the U.S., Canada, Australia, Latin America, or Israel.

ARTHUR ROTHSTEIN’S

PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE

HONGKEW JEWISH GHETTO

1946

In April 1946, Jewish American documentary photographer Arthur Rothstein created an indelible portrait of the Shanghai Jewish community. Rothstein’s photographs convey the refugee’s relief that the War was over, desperation to identify family members who survived, and anxiety of people who were once again being forced to migrate but were stranded in Shanghai. His photo essay provides a window into the lives of refugees who found tolerance and a temporary home during the turbulent years of World War II.

EXHIBITION GALLERY

CREDITS

Hidden History: Recounting the Shanghai Jewish Story

An Exhibit by Holocaust Museum LA

Sponsored by East West Bank Foundation and the Carl K. Moy and Linda C. Moy Family Foundation

Curated by Jordanna Gessler and Christie Jovanovic.

Graphic design by Brett Aronson. Illustrations by Dave Regan.

Artifacts from Holocaust Museum LA Archival Collection, and on loan from Skirball Museum, Yad Vashem, Mike Medavoy and Veronica Dressler, the Good family, the Kolber family, the Maskell family, the Millett family, and Dr. Ann Rothstein-Segan.